Remote Repositories

Last updated on 2025-12-03 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 0 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How do I connect my code to other versions of the it?

Objectives

- Learn about remote repositories.

https://www.atlassian.com/git/tutorials/syncing

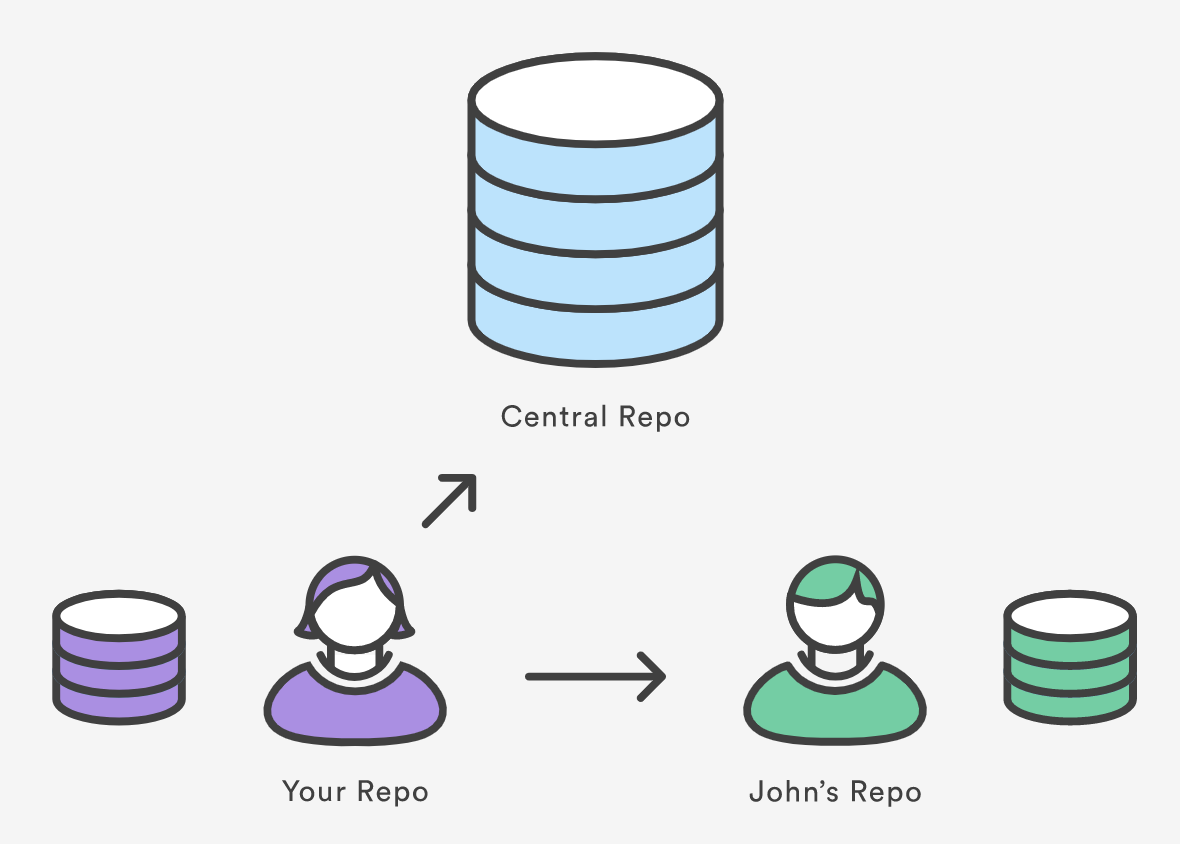

Git’s distributed collaboration model, which gives every developer their own copy of the repository, complete with its own local history and branch structure. Users typically need to share a series of commits rather than a single “changeset”. Instead of committing a “changeset” from a working copy to the central repository, Git lets you share entire branches between repositories.

Git remote

The git remote command lets you create, view, and delete connections to other repositories. Remote connections are more like bookmarks rather than direct links into other repositories. Instead of providing real-time access to another repository, they serve as convenient names that can be used to reference a not-so-convenient URL.

For example, the diagram above shows two remote connections from your repo into the central repo and another developer’s repo. Instead of referencing them by their full URLs, you can pass the origin and john shortcuts to other Git commands.

The git remote command is essentially an interface for

managing a list of remote entries that are stored in the repository’s

./.git/config file. The following commands are used to view

the current state of the remote list.

Git is designed to give each developer an entirely isolated

development environment. This means that information is not

automatically passed back and forth between repositories. Instead,

developers need to manually pull upstream commits into their local

repository or manually push their local commits back up to the central

repository. The git remote command is really just an easier

way to pass URLs to these “sharing” commands.

Adding a Remote Repository

Earlier, we created a repository on GitLab. Now, we need to connect

our local repository to that remote repository. The command for this is

git remote add:

You can find the repository URL on the main page of your remote

repository. It should look something like

https://gitlab.com/username/repository-name.git. The

location of this URL will depend on the hosting service you are using

(GitLab, GitHub, Bitbucket, etc.).

Most hosting services will provide the URL in two forms: HTTPS and SSH. If you are unsure which one to use, choose HTTPS. SSH requires additional setup which we do not cover in this training.

View Remote Configuration

To list the remote connections of your repository to other

repositories you can use the git remote command:

If you test this in our training repository, you should get only one

connection, origin:

When you clone a repository with git clone,

git automatically creates a remote connection called

origin pointing back to the cloned repository. This is

useful for developers creating a local copy of a central repository,

since it provides an easy way to pull upstream changes or publish local

commits. This behaviour is also why most Git-based projects call their

central repository origin.

We can ask git for a more verbose (-v)

answer which gives us the URLs for the connections:

Syncing with Remote Repositories

So we have a remote connection, but how do we make the code in our

local repository match the code in the remote repository? There are

three commands that we use to sync code between repositories:

git fetch, git pull, and

git push.

-

fetch- Downloads commits, files, and refs, but does not modify your working directory. This gives you a chance to review changes before integrating them into your local repository. -

pull- Downloads commits, files, and refs, and immediately merges them into your local branch. This is a convenient way to integrate changes from a remote repository into your local repository in one step. -

push- Uploads your local commits to a remote repository. This is how you share your changes with other developers.

Let’s use git pull to retrieve the latest changes from

the remote repository:

OUTPUT

$ git pull

remote: Enumerating objects: 3, done.

remote: Counting objects: 100% (3/3), done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (2/2), done.

remote: Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0), pack-reused 0 (from 0)

Unpacking objects: 100% (3/3), 2.74 KiB | 701.00 KiB/s, done.

From <REPOSITORY-URL>

* [new branch] main -> origin/main

There is no tracking information for the current branch.

Please specify which branch you want to merge with.

See git-pull(1) for details.

git pull <remote> <branch>

If you wish to set tracking information for this branch you can do so with:

git branch --set-upstream-to=origin/<branch> mainSo what happened? As we might have seen in previous sections, git

isn’t always clever, or at least it isn’t willing to make assumptions

about what we want to do. In this case, git is saying that it pulled

down changes from the remote repository, but it doesn’t know what to do

with them. This is because our local main branch isn’t set

up to track the main branch on the origin

remote.

We can use the suggested command to set up the tracking information:

This explicitly tells git that the local main branch is

the same as the main branch on the origin

remote. Now, if we run git pull again, git will know what

to do:

Viewing Remote Information

To see more detailed information about a specific remote connection,

you can use the git remote show command followed by the

name of the remote. For example, to see information about the

origin remote, you would run:

OUTPUT

$ git remote show origin

* remote origin

Fetch URL: <REPOSITORY-URL>

Push URL: <REPOSITORY-URL>

HEAD branch: main

Remote branch:

main tracked

Local branch configured for 'git pull':

main merges with remote main

Local ref configured for 'git push':

main pushes to main (fast-forwardable)It’s possible to have more than one remote for a given repository.

You can add additional remotes with

git remote add <name> <url>, and then view them

with git remote -v or

git remote show <name>.

This might be used if, for instance, you have a central repository

that you store your projects in, but also another repository that you

use for backup purposes. You could have remotes called

origin and backup, each pointing to different

URLs.

Pushing to Remote Repositories

We pulled changes from the remote repository, but if we refresh the

page on Gitlab, we won’t see our local commits there. If we run the

git status command we can see that git is aware that our

local branch has some commits that aren’t on the remote branch:

OUTPUT

$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is ahead of 'origin/main' by 9 commits.

(use "git push" to publish your local commits)

nothing to commit, working tree cleanLet’s use the git push command to upload our local

commits to the remote repository:

OUTPUT

$ git push

Enumerating objects: 28, done.

Counting objects: 100% (28/28), done.

Delta compression using up to 2 threads

Compressing objects: 100% (21/21), done.

Writing objects: 100% (27/27), 2.72 KiB | 696.00 KiB/s, done.

Total 27 (delta 4), reused 0 (delta 0), pack-reused 0

To <REPOSITORY-URL>

5be9f46..0622c3a main -> mainIf we now refresh the page on Gitlab, we should see our commits there!

The git remote command also lets you manage connections

with other repositories. The following commands will modify the repo’s

./.git/config file. The result of the following commands

can also be achieved by directly editing the ./.git/config

file with a text editor.

Create a new connection to a remote repository. After adding a

remote, you’ll be able to use <name> as a convenient

shortcut for <url> in other Git commands.

Remove the connection:

Rename a connection:

To get high-level information about the remote

<name>:

Exercise: Add a connection to your neighbour’s repository. Having this kind of access to individual developers’ repositories makes it possible to collaborate outside of the central repository. This can be very useful for small teams working on a large project.

Starting a branch from the main repository state:

Remember that when you create a new branch without specifying a starting point, then the starting point will be the current state and branch. In order to avoid confusion, ALWAYS branch from the stable version. Here is how you would branch from your own origin/main branch:

You must fetch first so that you have the most recent state of the repository.

If there is another “true” version/state of the project, then this

connection may be set as upstream (or something else).

Upstream is a common name for the stable repository, then

the sequence will be:

Now we can set the MPIA version of our repository as the upstream for our local copy.

Setting the upstream repository

Set the https://github.com/mpi-astronomy/advanced-git-training as the upstream locally.

Then, examine the state of your repository with

git branch, git remote -v,

git remote show upstream

Creating a branch and pushing it to the remote

Create a new branch in our local repository called

bean-dip and add the following recipe in a file called

bean-dip.md:

# Bean Dip

## Ingredients

- beans

## InstructionsAdd and commit the new file, then push the new branch to the remote

repository with git push. What happens? Can you find the

branch on the remote?

BASH

git branch bean-dip

git switch bean-dip

nano bean-dip.md

git add bean-dip.md

git commit -m "Add bean dip recipe."

git pushWhat happens here can depend on the version of git you are using. In more recent versions, git will automatically create the remote branch when you push a local branch that doesn’t exist on the remote. In older versions, you may need to specify the remote and branch name explicitly:

- The

git remotecommand allows us to create, view and delete connections to other repositories. - Remote connections are like bookmarks to other repositories.

- Other git commands (

git fetch,git push,git pull) use these bookmarks to carry out their syncing responsibilities.