Branches

Last updated on 2025-12-03 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 0 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What are branches?

- How do I view the current branches?

- How do I manipulate branches?

Objectives

- Understand how branches are created.

- Learn the key commands to view and manipulate branches.

Branching is a feature available in most modern version control

systems. Branching in other version control systems can be an expensive

operation in both time and disk space. In git, branches are

a part of your everyday development process. When you want to add a new

feature or fix a bug—no matter how big or how small—you spawn a new

branch to encapsulate your changes. This makes it harder for unstable

code to get merged into the main code base, and it gives you the chance

to clean up your future’s history before merging it into the main

branch.

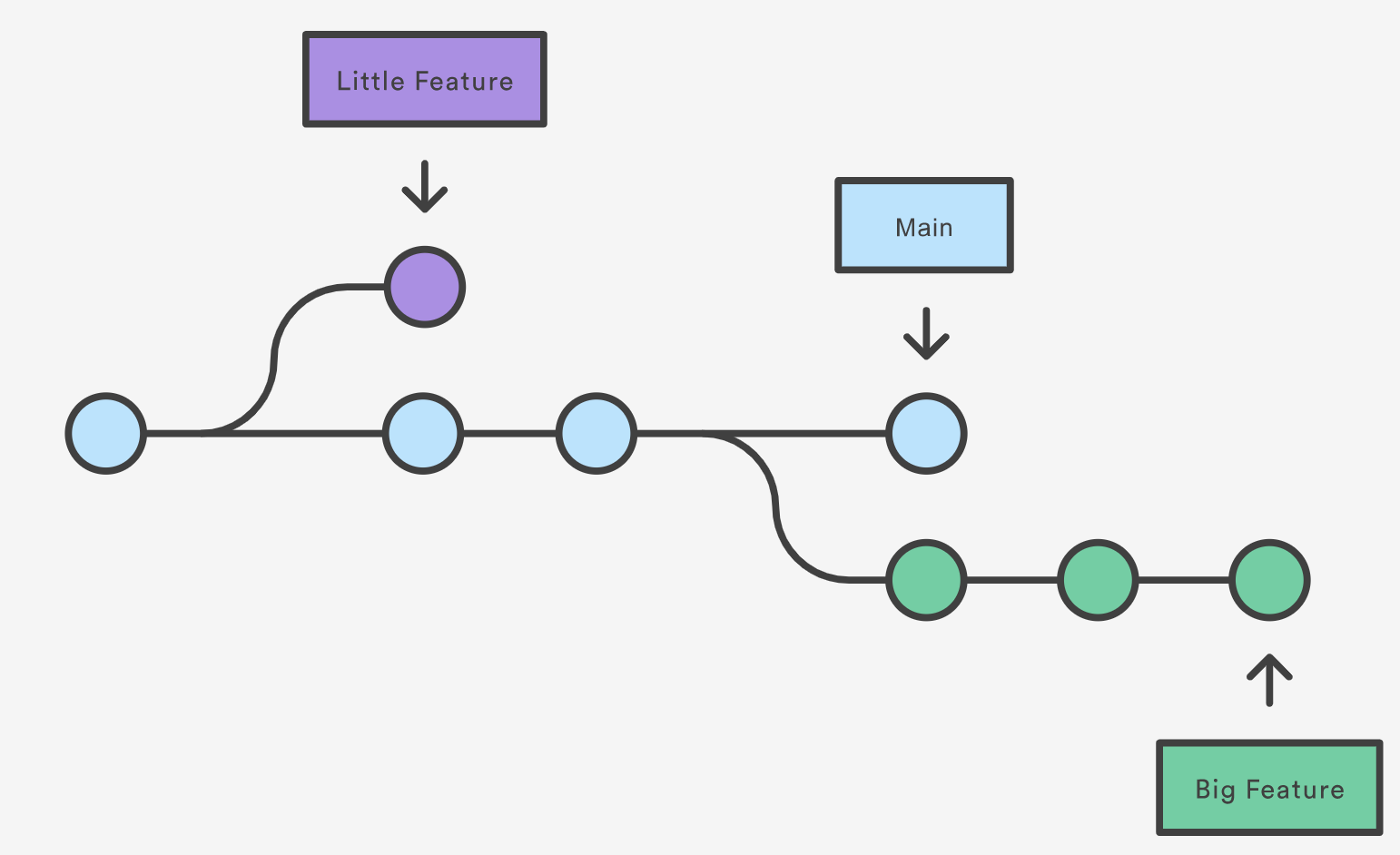

The diagram above visualizes a repository with two isolated lines of development, one for a little feature, and one for a longer-running feature. By developing them in branches, it’s not only possible to work on both of them in parallel, but it also keeps the main branch free from questionable code.

The implementation behind Git branches is much more lightweight than other version control system models. Instead of copying files from directory to directory, Git stores a branch as a reference to a commit. In this sense, a branch represents the tip of a series of commits—it’s not a container for commits. The history for a branch is extrapolated through the commit relationships.

()

What is a branch?

In git a branch is effectively a pointer to a snapshot

of your changes. It’s important to understand that branches are just

pointers to commits. When you create a branch, all Git needs to do is

create a new pointer, it doesn’t change the repository in any other way.

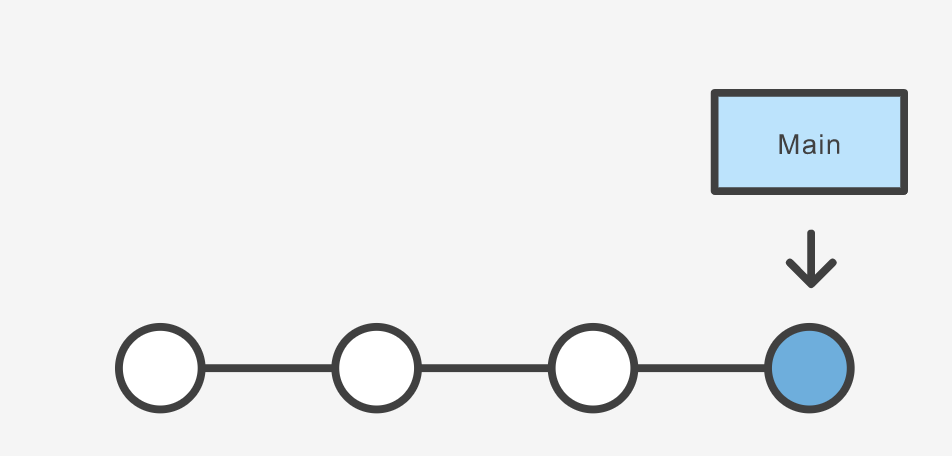

If you start with a repository that looks like this:

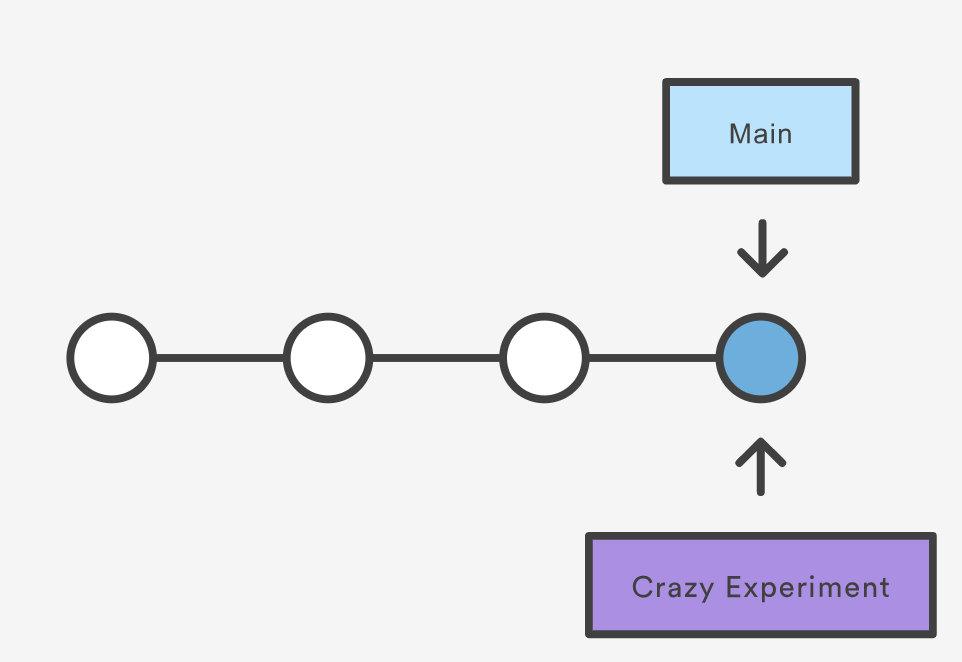

Let’s say we wanted to reworking our recipes to use a different format. We could continue on our existing branch, but we’re not so sure about this change, so instead we create a new branch to experiment with:

The repository history remains unchanged. All you get is a new pointer to the current commit:

Note that this only creates the new branch. To start adding commits

to it, you need to move to it with git checkout, and then

use the standard git add and git commit

commands.

A branch also means an independent line of development. Branches serve as an abstraction for the edit/stage/commit process. New commits are recorded in the history for the current branch, which results in a fork in the history of the project. However, it is really important to remember that each commit only records the incremental change in the document and NOT the full history of changes. Therefore, while we think of a branch as a sequence of commits, each commit is independent unit of change.

Branching Commands

Creating, deleting, and modifying branches is quick and easy; here’s a summary of the commands:

To list all branches:

OUTPUT

$ git branch

* main

yaml-formatThe asterisk (*) indicates the current branch. To see

more information about each branch, including the latest commit on each

branch, use the -avv flags:

OUTPUT

$ git branch -avv

* main ec240ab Ignore png files and the pictures folder.

yaml-format ec240ab Ignore png files and the pictures folder.We can see that, as we have not added any new commits to the

yaml-format branch, both branches point to the same commit

(ec240ab).

To create a new branch named <branch>, which

references the same point in history as the current branch.

To create a new branch named <branch>, referencing

<start-point>, which may be specified any way you

like, including using a branch name or a tag name:

To delete the branch <branch>; if the branch is

not fully merged in its upstream branch or contained in the current

branch, this command will fail with a warning:

To delete the branch <branch> irrespective of its

merged status:

Renaming a branch can be done with the -m tag:

Let’s switch over to our new branch so we can start making changes:

OUTPUT

$ git switch yaml-format

Switched to branch 'yaml-format'git switch was introduced in Git 2.23 as a more purpose

specific command for switching branches. It is functionally similar to

git checkout, which is still used widely, but is a more

general command with multiple purposes (switching branches, restoring

files, etc).

To create a new branch <new> referencing

<start-point>, and check it out.

The special symbol "HEAD" can always be used to refer to

the current branch. In fact, Git uses a file named HEAD in

the .git directory to remember which branch is current:

Let’s reformat our recipe to use YAML and commit the changes:

name: Guacamole

ingredients:

avocado: 1.35

lime: 0.64

salt: 2

instructions: ""Now let’s check our branches again:

OUTPUT

$ git branch -avv

main ec240ab Ignore png files and the pictures folder.

* yaml-format a2b55be Reformat recipe to use YAML.Challenge

Challenge 1: Renaming a file in a branch

We updated our guacamole recipe in the yaml-format

branch to use a different format. But now the file extension

.md doesn’t make sense anymore. Rename the file to

guacamole.yaml and commit the change to the

yaml-format branch. Run git status before you

commit your changes. Is there anything different about the way this

commit looks than in our earlier exercises?

OUTPUT

$ git status

On branch yaml-format

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

renamed: guacamole.md -> guacamole.yamlGit is not very clever about most things, but as long as the contents of the file are identical, it can at least figure out that we just renamed the file, rather than deleting one and adding another.

Challenge

Challenge 2:

- A branch represents an independent line of development.

-

git branchcreates a new pointer to the current state of the repository and allows you to make subsequent changes from that state. - Subsequent changes are considered to belong to that branch.

- The final commit on a given branch is its HEAD.